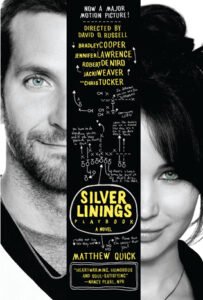

Matthew Quick is the New York Times bestselling author of THE SILVER LININGS PLAYBOOK, which was made into an Oscar-winning film; THE GOOD LUCK OF RIGHT NOW; LOVE MAY FAIL; THE REASON YOU’RE ALIVE; and four young adult novels: SORTA LIKE A ROCK STAR; BOY21; FORGIVE ME, LEONARD PEACOCK; and EVERY EXQUISITE THING. His work has been translated into more than thirty languages, received a PEN/Hemingway Award Honorable Mention, was an LA Times Book Prize finalist, a New York Times Book Review Editors’ Choice, a #1 bestseller in Brazil, a Deutscher Jugendliteratur Preis 2016 (German Youth Literature Prize) nominee, and selected by Nancy Pearl as one of Summer’s Best Books for NPR. The Hollywood Reporter has named him one of Hollywood’s 25 Most Powerful Authors. All of his books have been optioned for film. (author photo by Dave Tavani)

Matthew Quick is the New York Times bestselling author of THE SILVER LININGS PLAYBOOK, which was made into an Oscar-winning film; THE GOOD LUCK OF RIGHT NOW; LOVE MAY FAIL; THE REASON YOU’RE ALIVE; and four young adult novels: SORTA LIKE A ROCK STAR; BOY21; FORGIVE ME, LEONARD PEACOCK; and EVERY EXQUISITE THING. His work has been translated into more than thirty languages, received a PEN/Hemingway Award Honorable Mention, was an LA Times Book Prize finalist, a New York Times Book Review Editors’ Choice, a #1 bestseller in Brazil, a Deutscher Jugendliteratur Preis 2016 (German Youth Literature Prize) nominee, and selected by Nancy Pearl as one of Summer’s Best Books for NPR. The Hollywood Reporter has named him one of Hollywood’s 25 Most Powerful Authors. All of his books have been optioned for film. (author photo by Dave Tavani)

This interview was conducted in 2008. When Quick, a former teacher, decided to work on a creative thesis and earn an MFA, his first choice of schools was Goddard. “I had heard a lot about MFA programs producing nothing but highbrow, highly polished academic literary fiction that reads much like everything else that comes out of MFA programs,” he says. “Goddard’s emphasis on diversity and individuality really appealed to me. I think the Goddard catch phrase at the time was ‘Come as you are, leave who you want to be.’ A lot of other programs I looked at were not really saying anything like that. As a former teacher I had a pretty good idea of what I wanted out of an MFA program: self-directed learning that would allow me to take risks and follow hunches, and a safe environment in which I could make the mistakes we all need to endure if we are going to learn.”

GC: How does it feel to have a book on its way to large readership? Was this novel your first?

GC: How does it feel to have a book on its way to large readership? Was this novel your first?

MQ: Exciting. Surreal. A little scary. Although I had been working on the idea for a few years, I wrote the bulk of The Silver Linings Playbook as a side project during the third and fourth semesters of my Goddard experience, almost as a diversion from Goddard work. It was not my first novel. I had two shelved already and my Goddard creative thesis too. To be quite honest, I never dreamed that Silver Linings would eventually be picked out of the Sterling Lord Literistic slush pile, or that my book would be marketable in Italy and England, or that Sarah Crichton would love Silver Linings, or that there would soon be a buzz in Hollywood. The whole thing has blown my mind a little, or maybe a lot. It’s perplexing, because—other than to say my wife fell in love with the book and encouraged me to pitch widely—I couldn’t really tell you how it happened, nor do I know what to expect next.

GC: What made the difference, for you, between the two previous shelved novels and this successful one?

MQ: One of the things that happened in the fourth semester is that I made a transition. Richard, my advisor, said, “Where is the humor? This is so dark.” Halfway through the manuscript he commented, “Finally some humor.” When you first start writing you think you have to be the this very serious person with something important to say, but I think you start to realize that’s not necessarily what people want to read. I started to think about marketability. I tried to write something that was very much me, that would make my friends and family say “This is what Matt has been struggling with,” but structuring it for readers. When you first start writing you just want to dazzle. I started thinking about the craft. About entertaining. That’s what I got better at. Everyone is complaining about the fiction market and books not being read. If a tree falls in the forest and no one hears it, does it make a sound? If a book is written and nobody reads it, is it a book? I wanted to write something that my non-writing friends could pick up and enjoy. As writers, we shouldn’t feel guilty about wanting to entertain.

GC: What are you working on now?

MQ: A Young Adult book that is based on all of the research and writing I did for my Goddard creative thesis, although the plot and characters are entirely different. During my Goddard experience, my advisors—Rachel Pollack and Richard Panek—treated me like a real writer, which is to say they never let me get away with anything and always pushed me to make my manuscript better. During the fourth semester, both my advisors praised the risks I took with my Goddard thesis, but also helped me see the flaws. Richard used to tell me, “You can always work on your Goddard thesis post graduation,” which really was not what I wanted to hear at the time. I wanted to hear, “May I please have the honor of sending this world-altering manuscript to my agent pronto?” But the talks I had with my advisors continued to mold and influence me post-Goddard, and six months after I graduated my agent asked me to write a YA book. I had no idea what to write about, but I sat down at the keyboard and what came out reminded me a lot of what I was working on at Goddard. As I continued to write, one day I thought, “Finally, I understand how to make my Goddard thesis work!” I was off and running, and I’m almost done with the rough draft of that book.

GC: Your character, Pat Peoples, thinks his life is a movie produced by God, bound to end with a silver lining. What do you think of this very close connection, in fiction and your life, between the novel and the film? Have you found the silver lining?

MQ: When I decided to write full-time, after consulting with my wife for months, I quit a tenured position at a prestigious high school, sold my house, moved into my in-laws’ home, and wrote in their basement every day for three years. My parents thought I had gone mad. Some friends quietly disapproved. People kept asking what I was doing in the basement, and when I was going to get a ‘real’ job. And it was hard, because at times I wasn’t sure that I was doing anything productive at all. It’s a wild thing to write in your in-laws’ basement for three years, not knowing if you will ever publish. Two things gave me hope: my wife’s constant encouragement and—as stupid as it might sound—looking up at clouds during my daily sunset runs. Considering all I had sacrificed, all the work I had put into this process, the silver lining had to be coming, right? More than eighty agents rejected my pitch letter and sample chapters. Fifty more never even responded. The one referral I managed to finagle from a respected published writer went nowhere and ended in polite rejection. I was just about to give up; I was getting my C.V. together, soliciting letters of recommendation, and looking for a teaching gig when I got a call from Doug Stewart of Sterling Lord Literistic. And then the real-life silver lining began to manifest. The way things played out—especially given the title of the book—made me pause and reflect. I won’t suggest that it was some sort of divine plan, but maybe inevitability really does exist if you work hard and look at the world with the right eyes.

GC: How did your time at Goddard affect your work as a writer?

MQ: First, my advisors Rachel Pollack and Richard Panek are both incredible people and wise teachers. I learned so much from both of them. They, like the Goddard program itself, allowed me to take risks and make mistakes and grow in whatever direction I wanted to grow. To have my work read and commented on by such brilliant writers and thinkers helped me take myself seriously, and taught me that my words really do have value. I also was absorbed by an eclectic group of fellow students very early on in my Goddard career. Without a doubt, this group is the most diverse social network of which I have ever been a part. I met and befriended many people at Goddard who did not think like me, but were willing to listen to what I thought and exchange ideas. Ten months after ‘my group’ graduated, we still e-mail almost daily. Most importantly, at Goddard I felt like I could be the person I had always wanted to be, and that I could write all of the things I was afraid to write. Being part of a community of writers for the first time in my life helped me to feel like less of a freak, and more like a writer.

GC: What was the most difficult part of the writing process for you?

MQ: The most difficult part of the writing process was and is sending my words into the world. Writing is a very personal, therapeutic, and maybe even spiritual process for me. And the emotions I feel when I am sitting alone writing are very intense and often not what I show people face-to-face. But writing is an act of communication, and an act of faith—trusting the reader to be someone who is willing to shake the hand that comes up out of the page. Sometimes it’s hard to believe that I really should be showing people all these naked words I try to write passionately and bravely and honestly, that it does matter and writing fiction is not a waste of time, or a self-indulgent act. Believing that I really do have something to offer people, and that people need and will want what I send out into the world, that’s the most difficult part of the writing process for me. It’s a daily battle.

GC: How did Goddard help in the battle?

MQ: When you decide to write there’s a lot of people who make you feel like you’re doing something frivolous. The MFA validates your work, says it isn’t foolish. Legitimizes it. The world is a dangerous place for writers. People make you think you shouldn’t write, you shouldn’t have a voice. Goddard makes it your responsibility to write, to have a voice. That’s a cool thing.