Bulgakov, when faced with the prison-like conditions of Stalin’s reign of terror closing around his country wrote his masterpiece in private, for no money or fame. His only wish, according to a note he left in his journal in 1931 was: “Lord, help me to finish my novel.” He died in 1940, long before the atrocities became known and condemned by the world.

Since the national election in November of last year, and in particular since 20 January of this year, I have felt bouts of disbelief, confusion, fear, powerlessness, and anger: hardly the right state-of-mind to write a commencement speech which by tradition calls upon the speaker to offer hope, inspiration, good cheer, and confirmation of the bright future to graduates.

Since the national election in November of last year, and in particular since 20 January of this year, I have felt bouts of disbelief, confusion, fear, powerlessness, and anger: hardly the right state-of-mind to write a commencement speech which by tradition calls upon the speaker to offer hope, inspiration, good cheer, and confirmation of the bright future to graduates.

I say this because I don’t wish to pretend all is well, but nor do I want to ring a doomsday bell. Like you, I’m a devotee of letters and the Imagination, of Imaginative Literature, and what I have to offer you, writers, poets, dreamers, storytellers, keepers and people of the Word, in addition to my steadfast belief in the human capacity for love, are some thoughts on books and writing and art, for in my loss of what say to you, and in my great worries about the times we live in, no doubt many years in the making but now firmly upon us as we face the consequences of our creations and of our politics, I returned over the last months to the library to seek in solitude and quiet the wisdom, the beauty, the truth and company in books—my great home since I was a child in Los Angeles adrift in a world of TV and spectacle and vapidity and a deep unarticulated loneliness and out-of-placeness, where I learned and loved to read and found in literature the wild connections, understanding, and a chorus of voices which spoke to me then across time, space, culture and language, and encouraged and emboldened me, and continue to do so until today. I speak to you, one writer to another, without easy answers in my pocket that might be easily digested, easily packaged for consumption, and as easily forgotten—for ours has always been and remains the work of reflection, complexity, of individual vision set up in deep contemplation of the world and manifested through and via determination, a calling, a love for words and stories, and an abiding hopefulness in the human and non-human — in life — and in what the scholar Henry Corbin called “the Mundus Imaginalis”: the imaginal world. For what really keep us for years on end in our chairs, at our desks, except a drive which we ourselves cannot perhaps fully understand or even articulate, which the poet Rilke simply called “I must,” when asked why write, to create from nothing the some things of literature: stories, poems, memoirs, plays, novels, books.

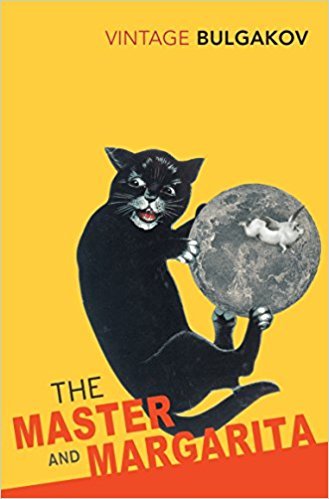

I returned to Emerson, Italo Calvino, George Orwell and Lorca among others over the last few months, and then only last week to a book whose opening scene was haunting me, to Russian writer Mikhail Bulgakov’s wondrous and hilarious satiric masterpiece, The Master and Margarita, a novel about the chaos that ensues when on “one hot spring evening” Satan arrives in Moscow. The devil, called Professor Woland, is more or less a trickster figure, a “magician” who brings with him a colorful retinue including a giant gun-toting, vodka-drinking talkative black cat and a naked witch and the group wreaks havoc on the bureaucrats, the venal literary elites and generally on all whom they encounter revealing the prevailing greed, vanity, hypocrisy, and gullibility of society.

Bulgakov wrote the novel during the 1930s, one of the darkest decades in Russian history, when Stalin consolidated his power by killing and purging anyone he deemed his enemy or what he called “enemies of state.” Between ten and twenty million people were sent to the gulag (the labor camps); one million people in the communist party were killed outright; he purged the army of its generals, and most of the Communist Party of its leaders. There were show trials for the so-called traitors who had to admit their guilt publicly; artists, intellectuals, anyone Stalin deemed potential enemies were blacklisted and lived in fear for their lives. Bulgakov, the most famous playwright of his generation, had all his plays banned by 1929. After that, he was no longer allowed to publish and worked on his novel for ten years with full understanding that he would never live to see its publication and that if anyone got wind of it it might mean for him either banishment or death.

Why speak to you today of a dark period in history when we have gathered to celebrate, of Bulgakov, who maybe some of you have never even heard of; why speak of the devil? I returned to Bulgakov’s work not only for its hilarity, its stunning achievement as imaginative literature, but because I have been thinking a lot, as perhaps you have, as Bulgakov did in his lifetime: what is the artist’s responsibility and duty in his/her time? What is my responsibility? What is yours? And to add to that: is art necessary? In Bulgakov’s lifetime, writers were reduced to being mouthpieces of the state or they were silenced, or worse. What about us? We don’t have strong censorship laws (yet) and for now I don’t see writers being jailed for their writing, but I do wonder if art and literature have in some measure been reduced to mere entertainments, have lost their power in the hullabaloo of social media, a barrage of news sites, propaganda (what some call ‘alternative facts’), TV shows, movies, and video games that inundate our conscious lives. (The average screen time for Americans, by the way, is 74 hours a week). Neil Postman, the media theorist, worried about Americans “amusing ourselves to death.” He warned in 1986: “Everything in our background has prepared us to know and resist a prison when the gates begin to close around us … [but] who is prepared to take arms against a sea of amusements?”

Bulgakov, when faced with the prison-like conditions of Stalin’s reign of terror closing around his country wrote his masterpiece in private, for no money or fame. His only wish, according to a note he left in his journal in 1931 was: “Lord, help me to finish my novel.” He died in 1940, long before the atrocities became known and condemned by the world. His widow published his book twenty-six years later and it became and remains until today one of the most popular books in Russia. What did he do in his book? He left us encoded in this beautifully imagined work of art a great resistance to tyranny through beauty, art, love and laughter: we laugh with the devil and his entourage as they wreak habit on an absurd, corrupt system. The magic and wonder in the book allow the reader to acknowledge other possibilities outside of a reality of political repression, poverty, and war.

Part of my response to the times I live in has been to return to books. To find solitude, quiet, and reread The Master and Margarita and in this way deeply engage with the world. Perhaps we can say reading is a kind of service, for not only does it increase cognitive power, it increases our sympathies, our capacity for understanding ourselves and others: when we read our consciousness aligns with that of the book and this has the radical potential for the beautiful expansion of our imagination. Or as Calvino said, “Literature is like an ear that can hear things beyond the understanding of politics; it is like the eye that can see beyond the color spectrum perceived by politics. Simply because of the solitary individualism of his work, the writer may happen to explore areas that no one has explored before, within himself or outside, and to make discoveries that sooner or later turn out to be vital areas of collective awareness.” Calvino himself came of age in a time a dictatorship and war in Italy.

In addition to reading of course, what is our duty? To Write. Emerson said in his essay On Poetry:

Doubt not, O poet, but persist. Say, “It is in me, and shall out.”

Bulgakov persisted. Calvino persisted. Which is to say, as I always say: do your work. The joyous, troubling, unsettling, meaningful, mysterious, prophesying and vital work of discovering and writing stories, of mapping human life and consciousness and hopefulness and tragedy, and the invisible world and of bearing witness to your times in symbolic form, of being an “eye” and an “ear,” and of always saying to the world as the artist does in her way, via her vision, a wild, complex, enthusiastic, life-filled: yes! I think this is your job, writers. We are officiants at the world table of letters and ours is to add to the great ecology of stories. Not only as amusements—although as in Bulgakov’s book we may very well write the absurd and funny—but not to distract us from the world, rather that we may know it more clearly.

This speech was delivered at commencement for the MFAW Program in port Townsend, WA on February 12, 2017, and is being reposted here. The photo is of Mikhail Bulgakov.

Micheline Aharonian Marcom

Latest posts by Micheline Aharonian Marcom (see all)

- IMAGINATIVE LITERATURE - April 6, 2020

- Imaginative Literature in Dark Times - November 5, 2018

- I Don’t Know Where to Begin… - September 6, 2017

- Imaginative Literature - March 6, 2017

- The New American Story Project - October 31, 2016

Brilliant the first time I read it and freaking brilliant now, today. Thanks for the loveliness which is always there, yet sometimes hard to access!